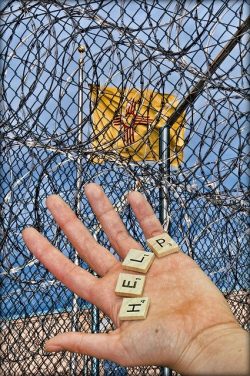

Should Methadone Be Given to Inmates Addicted to Opioids?

Michael sat in his cell. He felt like he was burning up with a fever, but he was freezing at the same time. His muscles ached, and he was anxious. No, it wasn’t COVID or the flu. Michael was in opioid withdrawal.

Michael had been on methadone for two years. He’d taken an 80mg dose every day for 24 months – until three days ago. That’s when he got in a fight and ended up in jail for assault. Now he’d missed three doses and didn’t know when (or if) he’d be able to receive methadone while he was locked up.

Before he started methadone treatment, he’d experienced opioid withdrawal when he couldn’t get heroin for a day or two. But methadone withdrawal when you go cold turkey is a completely different animal – he knows a guy who had seizures after going cold turkey.

Michael didn’t know if he could handle it. He asked one of the guards about getting his medication, but the guard blew him off. Now Michael was sick and feeling hopeless. He started thinking it might be better to just end it all.

Call 800-994-1867 Get Help Now - Available 24/7Continuing Methadone Treatment in Jail is Rare

Will Michael get the methadone treatment he was receiving before his arrest? Odds are that he won’t. Only about 30 percent of jails in the United States provide inmates with medication-assisted treatment for addiction.

Will Michael get the methadone treatment he was receiving before his arrest? Odds are that he won’t. Only about 30 percent of jails in the United States provide inmates with medication-assisted treatment for addiction.

Why? Several reasons. First, some officials say the cost is too high. It requires a lot of staff, time, and space within the facility to provide the daily doses of methadone. Second, jail administrators want to be careful about allowing drugs into their facilities. If they prescribe methadone to inmates, there’s a risk the medication could be sold to other inmates.

Despite these challenges, the number of jails that offer methadone treatment has grown in recent years. In fact, the number of jails and prisons systems offering evidence-based treatment for opioid addiction has tripled since 2018.

What’s turning the tide? The numbers.

Staggering Statistics

There are roughly 1.5 million inmates in the U.S. currently addicted to alcohol or drugs. And in the first two weeks after release, prisoners are 40 times more likely to die of an opioid overdose than the general population.

Why are these overdose numbers so high? When inmates are locked up and forced to abstain from drugs, they lose their tolerance. That means the body adjusts to not having drugs in its system.

When inmates are released, they go back to using the same amount of opioids they used before getting arrested. But since their tolerance is gone, they often overdose – and it’s often fatal.

Call 800-994-1867 Get Help Now - Available 24/7Is Methadone the Answer?

Some research indicates that providing addiction medication to inmates could decrease these overdose numbers. In Rhode Island, one medication assisted treatment program “reduced overdose deaths among the recently incarcerated by more than 60 percent.”

Some research indicates that providing addiction medication to inmates could decrease these overdose numbers. In Rhode Island, one medication assisted treatment program “reduced overdose deaths among the recently incarcerated by more than 60 percent.”

And, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, “decades of science shows that providing comprehensive substance use treatment to criminal offenders while incarcerated works, reducing both drug use and crime after an inmate returns to the community.”

Policy makers who want more prison systems to offer methadone treatment point to these numbers and call for change. They argue that providing methadone would improve conditions both inside the prisons and in the lives of inmates after their release.

Toronto-based doctor Sharon Cirone specializes in mental health and addictions. She says that methadone and other opioid-substitution therapies should be a top priority for inmates. Cirone compares the medication to others for seizure disorders and heart disease.

“Methadone and Suboxone and other treatments of opioid-use disorders deserve the same attention,” she noted.

Cirone was recently called upon to testify in an inquest. The proceedings are looking into the death of an inmate who had been taking methadone for six years before his arrest. The inmate, Aaron Moffatt, did not have access to his daily dose of methadone while in prison. Moffatt hanged himself in his cell a few days after incarceration and died two weeks later in the hospital.

Cirone pointed out that there must be “continuity of care when people are taken into custody.” Her advice: “There should be no gaps in care of methadone provision. Period.”

If you or someone you love is experiencing a substance use disorder, help is available. Call 800-994-1867Who Answers? today.